Editor’s Note: Bishop Meade’s complicity and his overarching theological views on human dignity as it relates to people of color was largely excluded from the initial version of this article as it first appeared on our diocesan website and social media. We acknowledge that the larger body of Bishop Meade’s theological and personal thought regarding the enslaved, and the significance of their lives, is incompatible with our understanding of human dignity. Bishop Meade did not believe that slaveholding itself was morally wrong, and never publicly criticized the predominate economic institution of Virginia; in fact, he provided it with a robust theological justification that we now acknowledge as theologically damaging, especially in light of our Baptismal Vows. His failure to morally critique enslavement as sin was entrenched in a paternalistic theology that, at best, was racially driven at that time. As an elected leader of our diocese, Bishop Meade holds particular significance in our history and so therefore the discovery of these portraits is also significant; and, it is important that any reporting of history be given full context.

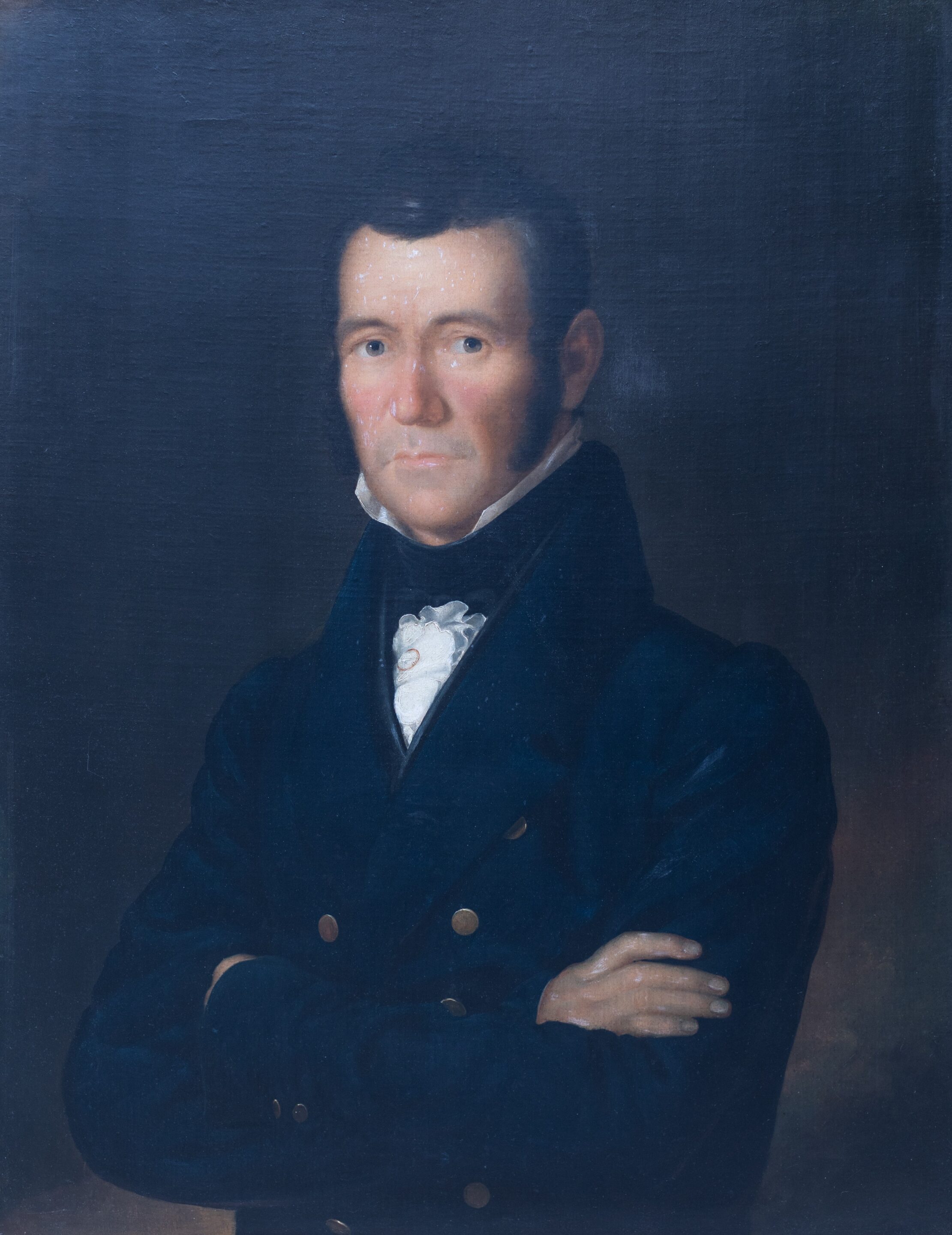

The Rt. Rev. William Meade (1789-1862) lived long before the age of selfies and photography. Few knew what the third Bishop of the Diocese of Virginia looked like as a young man until his large oil portrait, and his wife Thomasia’s, showed up in the backseat of a Subaru in Richmond this year.

The portraits were a gift from his descendants to the Diocese of Virginia.

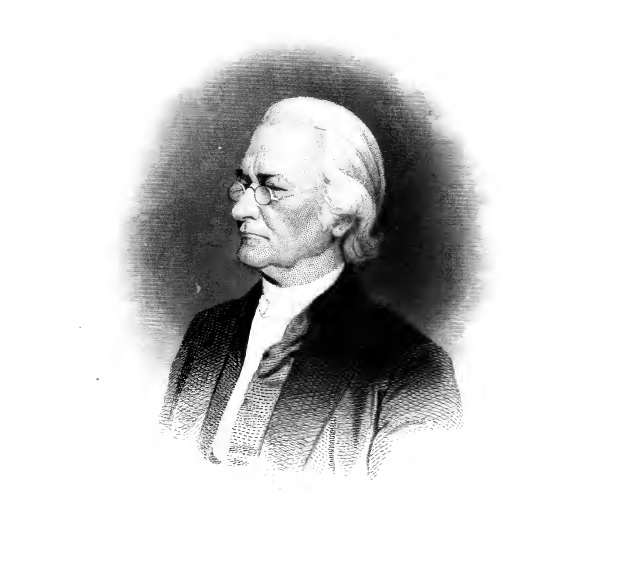

“We have a lot of drawings and engravings of Bishop Meade when he was older; this is the first time we’ve had a painting of him when he was younger, and as far as his wife, I do believe this is the first image we’ve had of her, the first I’ve ever seen,” Diocese historiographer and registrar Nathan V. Madison said.

The paintings are just shy of 200 years old, Madison estimated.

“What a stroke of luck!” he said. “That someone several states away but with familial ties to Virginia, happened to have portraits, unique in so many ways, of a bishop and his spouse whose portraits we were lacking! And that they were generous enough to donate them to the Archives and ‘bring them home,’ as it were. A great experience and an amazing gift to the Diocese itself.”

For donor Jaye Richey, who is 80, handing off the portraits brought on “a mixture of relief, a little sadness. I knew in my heart it was the best thing we could do.”

A Significant History

A founder of Virginia Theological Seminary, Bishop Meade was “an interesting and complicated, but nonetheless important figure in the Diocese’s history,” as well as to the history of Virginia, according to Madison.

“The third Bishop of Virginia, with an episcopate lasting from 1841 until his death in 1862, was a prolific writer. One of his works in particular, Old Churches and Families of Virginia (1857), remains an invaluable source regarding both Diocesan and state history, and has seen a number of reprints over the last century and a half,” Madison said.

“He fought against several ideas that were spreading through some churches at the time, particularly those of the Oxford Movement. Near the end of his episcopate, though an opponent of secession, he did side with the Commonwealth of Virginia and the Confederacy during the Civil War. He aided in the formation of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America, participating in that church’s only consecration of a bishop during its brief existence.”

Bishop Meade’s views on chattel slavery are regrettable and profoundly harmed the theological and spiritual mission of the Church. However, they were not an isolated personal failing as they were in line with a large sentiment of the Episcopal Church at the time. This perspective held that enslavement was not a sin or a moral evil, but rather served a Christian, paternalistic role for the Southern slaveowner. The institutional depth of this complicity notes that in 1860 no less than eighty-four of the 112 active members of the clergy in the Diocese were slaveowners.[i] As late as January 1865, the Southern Churchman’s editors were quoting religious leaders arguing that slavery should be a “permanent institution of the South…made to conform to the law of God.”[ii]

Additionally, it should be noted that as early as 1813, then Rev. Meade compiled and edited several tracts explaining what he understood to be the “correct” manner with which a slaveholder should treat the enslaved, describing such acts as “charitable work.”[iii] Bishop Meade couched the issue of slavery in terms that suggested that the enslaved were beyond simple political concerns, but rather a question for Christian mission and order in the world–with a primarily goal of Christian conversion followed by “abolition and deportation” back to Africa.[iv]

In the summer of 1856, he penned an editorial wherein he sought to defend himself from accusations of abolitionism following a sermon during which he praised the confirmation of several African American members of a Lawrenceville congregation:

God… had given us a religion suitable to all, and that the bible had many things addressed to all, rich and poor, bond and free – that the larger portions of the human race always been in some form of bondage to the other, being poor and dependent, that God in his providence had permitted a large number to come this country from Africa, intending to make it a blessing to them, their posterity and Africa itself, by bringing them to the light of the Gospel, and sending the Gospel back to that country…[v]

In summary, while Bishop Meade in his youth “emancipated the enslaved he had inherited,” he used his significant authority and influence to propagate a theology that stripped people of color of their inherent human dignity—advancing a paternalistic rationale of Christian piety, and a morally indefensible and deeply destructive theological framework that religiously undergirded the institution of slavery.[vi]

Need for Meades

“Who wants the Meades?” Richey asked her children as she prepared to make changes to her small Cape Cod-style home in Riverside, Conn., near Greenwich.

When no one expressed interest, Richey decided that “it was time to take them back home.”

The portraits represented her late husband Samuel Hunter “Spike” Richey II (1944-2022)’s long-ago family connections to the South. He was a cradle Episcopalian who loved to sing in the choir. She soon joined the church.

While the family moved often and lived for a time in the South, they always identified as Northerners. “We are all displaced Yankees,” she said.

Her husband’s father was John Meade Richey (1920-2004). The portraits changed hands before resurfacing one summer when his stepmother called from Long Island “and announced that she had these portraits, and would we like them?” Jaye Richey recalled.

All their walls were covered with pictures, but the Richeys went to get the Meade portraits and make space for them in their TV room. The paintings were heavy from the oil and multiple ornate frames from later restorations. In their Connecticut home, they hung out for about a dozen years, facing the TV and a bookshelf.

“You blend it into the home,” Richey said. “I knew how important these portraits or people were to him and had been to his dad and grandparents. I know he was happy to have them. I grew used to them and liked them.”

The painter did not sign the portraits, and Richey didn’t see any resemblance passed down through her husband. She eventually read about Bishop Meade and was impressed by the distances he traversed in an era when Virginia stretched to the Ohio River.

“Talk about business trips,” she said. “When your Sundays are covered, it takes all of Saturday to get there, and most of Sunday afternoon to get home. You cover a lot of ground. That’s a commitment.”

Outstanding Artifacts, Personality Insights

Madison called the portraits “outstanding artifacts to have received, on any number of levels.”

“I was struck by a few things, most of all though the quality and detail of the portraits,” he added. “Just from looking at their portraits, you can almost get a sense of who these people were, their personalities; just remarkably well painted. These were apparently personal paintings, as opposed to ‘official’ Diocese portraits, so I also believe you get a little more of the ‘person,’ as opposed to the office, in Bishop Meade’s portrait.”

Such a personal depiction at this age helps to understand William and Thomasia Meade more fully.

“Most of the imagery we have of Bishop Meade is from his later years,” Madison said. “These portraits, however, were painted when he was younger – judging from the style of dress, his apparent youth, and the fact that his wife was painted as well, I believe these were produced during his time as Assistant Bishop, between 1829 and 1836, the year Thomasia died, and several years before he became Bishop Diocesan.

“The fact that we also have a portrait of Thomasia, the only portrait of a bishop’s spouse in our collection, and the only image I’ve seen of her in general, is also amazing,” Madison added.

“In 1857, Bishop Meade published a small, limited-run book entitled Recollections of Two Beloved Wives, which provides emotional insight into Meade as a man, but it also provides such a wealth of information regarding Thomasia, who she was and her role in her husband’s ministry. Thanks to her portrait, we can now apply a face to the person.”

Madison is curating a museum space on the third floor of the diocesan offices with, among other things, portraits of all of the bishops of Virginia – now including the Rt. Rev. William Meade oil portrait. A new section of portraits will detail the roles women have played in the history of the Diocese “and my goal is to have Thomasia placed there, as well, so both can be publicly viewed,” he said.

[i] Edward L. Bond and Joan R. Gundersen, The Episcopal Church in Virginia, 1607-2007 (Richmond: The Episcopal Diocese of Virginia, 2007), 104.

[ii] The Daily Dispatch. (Richmond, VA), Jan. 30 1865.

[iii] Rev. William Meade, ed., Sermons Addressed to Masters and servants, and Published in the Year 1743 by the Rev. Thomas Bacon, Minister of the Protestant Episcopal Church in Maryland Now Republished with other Tracts and Dialogues on the Same Subject, and Recommended to all Masters and Mistresses to Be Used in Their Families (Winchester: John Heiskell, 1813), iv.

[iv] Jennifer C. Snow, Mission, Race, and Empire: The Episcopal Church in Global Context (New York: Oxford University Press, 2024), 114.

[v] Richmond Enquirer. (Richmond, VA), Jul. 8 1856.

[vi] Jennifer C. Snow, Mission, Race, and Empire: The Episcopal Church in Global Context (New York: Oxford University Press, 2024), 114.