Racial justice and healing, as envisioned by the Episcopal Diocese of Virginia, means boldly speaking truth to power.

A piercing portrait exhibit at Trinity Episcopal Church captures what that looked like in Charlottesville in the Jim Crow 1920s: resolute, proud faces of local African Americans, some of whom had once been enslaved.

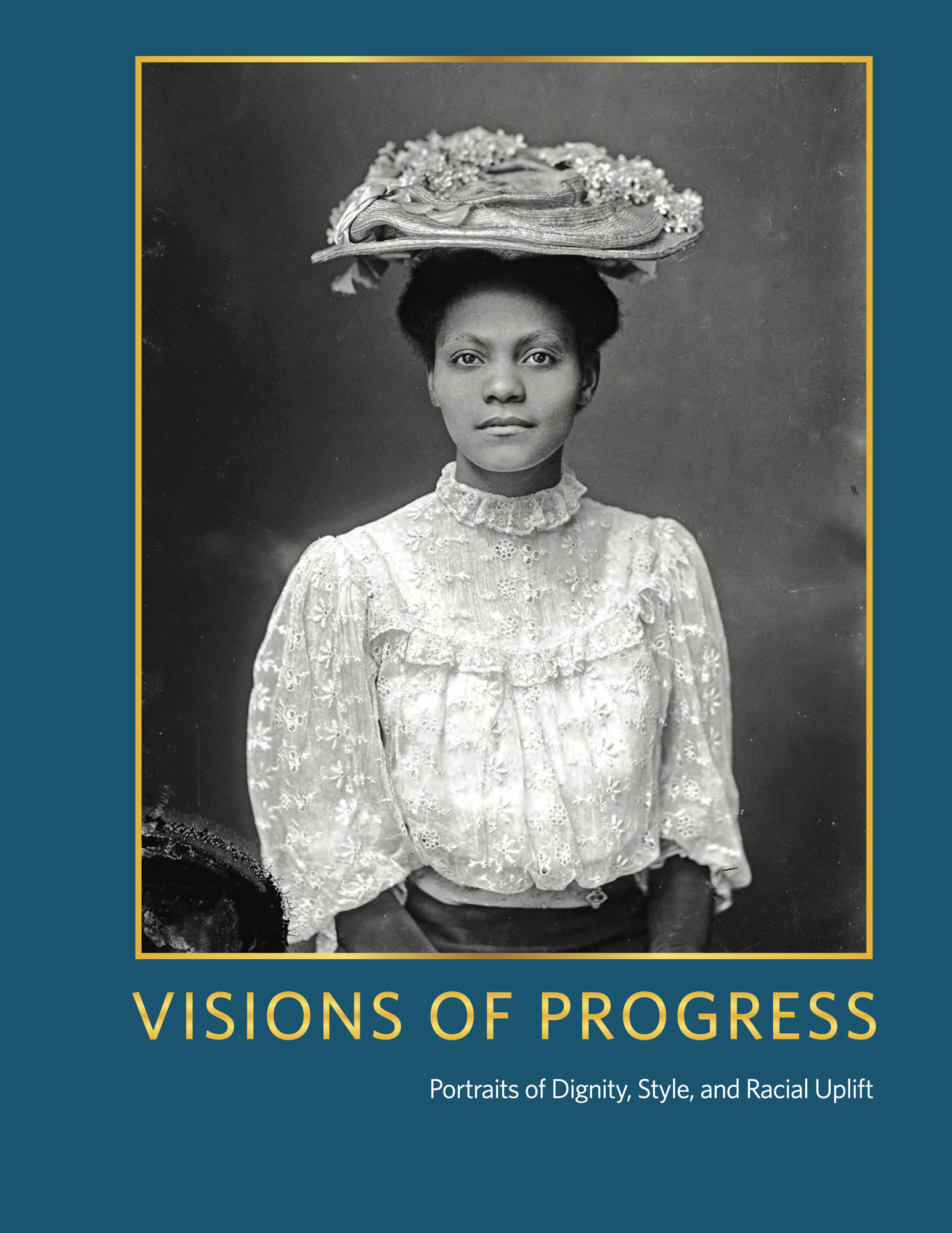

“Visions of Progress: Portraits of Dignity, Style, and Racial Uplift” fills walls with images from the acclaimed exhibit of the same name at the University of Virginia (UVA). They depict a generation who silently yet powerfully asserted the Black community’s claims to rights and equality.

“When I first saw the exhibit at UVA I knew it had to be at Trinity given our history and programming around racial reconciliation and racial healing,” said Rector Cass Bailey.

Trinity regularly turns its parish hall into exhibit space for artists in its congregation and from the community, and this is the sixth exhibit in the past 2.5 years, Bailey said.

“When I walked into the parish hall after it was hung, I was overwhelmed with pride. These images really demonstrate how African Americans in the South felt about themselves despite what others thought of them and how they were treated.”

Connected to Trinity

Parishioner John Edwin Mason, UVA professor emeritus of history, curated the Visions of Progress. He said the portraits complement the work of racial justice and healing in the Diocese of Virginia, “re-examining its history that relates to slavery, segregation, and its participation in and support of white supremacy.”

The portraits represent “part of that history that needs to be rediscovered, brought to the surface. In this case, it is not really a history of repression, but it’s a history of resilience, of strength. It’s a history of refusing to accept the place that the world has defined for you. And there’s no question that spirituality was an important part of this.”

Mason believes many of the portraits are of Trinity members, but without a list of parishioners from that era, he can’t be sure.

Most portraits show people posing in the studio in their Sunday best, but some are on location. One portrays five African Americans sitting in a field outside a house in Kellytown, near Trinity’s current location at 1118 Preston Ave.

“A high school baseball player with a good arm could throw a baseball from Trinity to where that house was,” Mason said. “It’s been slightly frustrating that there’s no picture of the old Trinity in this collection. There are two old Trinitys. There’s no picture of either one.”

Mason’s interest and influence in African American history in Virginia is professional and personal. His father, The Rev. John Edwin Mason, was born in Brunswick, Va., and attended St. Paul’s College. After a military career and seminary, the elder Mason served several parishes and as canon at Christ Church Cathedral in St. Louis.

Mason was drawn to Trinity for its commitment to “an intentional, multicultural community of reconciliation, transformation and love.”

“I moved to Charlottesville in 1994 and somebody told me there’s a historically Black Episcopal Church in town,” he recalled. “I went to it and it felt good. And, you know, for the first time, I found a place that felt like it could be a spiritual home for me.”

In 1999, UVA obtained 10,000 glass plate negatives from Holsinger, the main portrait studio in Charlottesville. Of those, 500 depicted African Americans, most of whom were named in the studio’s ledger books.

Mason had been writing extensively on early 19th century South Africa history, especially the history of slavery, and the history of photography.

The Holsinger cache “got me thinking and learning about the power of photography to tell stories and to tell history,” he said.

History Meets Opposition

In 2015, Mason began the portrait project, shortly before the city of Charlottesville tapped him in its pursuit of a fuller version of its history.

In 2016, Mason began serving as vice chair of the City of Charlottesville’s Blue Ribbon Commission on Race, Memorials, and Public Spaces. This committee recommended that the city should either remove or transform and contextualize its statues of Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson.

In 2017, opposition crested when white nationalists rallied in Charlottesville and a counter-protester was killed and dozens others injured.

In early 2020, the UVA Special Collections Library invited Mason’s research team to mount an exhibit of the Holsinger portraits. The resulting exhibit in 2022 and 2023 drew a record number of visitors to the library.

“We knew that these portraits had a way to change the way that people see the history of this place,” Mason said. “Nobody could imagine that African Americans at the height of the Jim Crow movement, looked like this, presented themselves to the camera with such style and fashion and poise and respectability.”

Each portrait can be seen as a small act of resistance to the racist caricatures in that era.

“The images are fantastic when put next to your knowledge of the intense segregation of this period, of the fundamental denial of not just constitutional rights, but human rights,” Mason said.

“They were made when there were lynchings in Charlottesville area, when African Americans were barred from most kinds of upward mobility. They could only have jobs like being a laundry woman, janitor, somebody’s cook or nanny, being a go-fer in a store or a porter.

“But that oppression did not define these people’s lives because in these portraits they’re telling you, ‘We are not who the white community thinks we are, and we are not defined by our oppression.’”

The energy and determination in the portraits reflect the “New Negro” progressive movement during the Jazz Age that influenced massive social change. “The civil rights movement literally stands on the shoulders of people in the portraits,” Mason said.

Of the exhibit at his home parish, he added: “I’m honored. I’m really happy that our rector also understands the significance of these portraits and how important this exhibition is. That’s gratifying and so is the fact that just this many more people will see it because it’s at Trinity.”

Viewing the Portraits

The portraits will be on display until March 11, and visitors who want to come on a day other than Sunday should contact the church.

For those who can’t visit in person, an online catalog is available as a free download.

“It will give you a good sense of what the portraits look like as well as what they tell us about the history of the region, the state, and the nation,” Mason said chief curator John Edwin Mason, UVA professor emeritus of history. Hard copies of the catalog were distributed to libraries, schools and historically Black churches.

“Our goal with this project, from the beginning, has been to change the way that people see the history of the early 20th century. So, we want to get the catalog into as many hands as possible.”