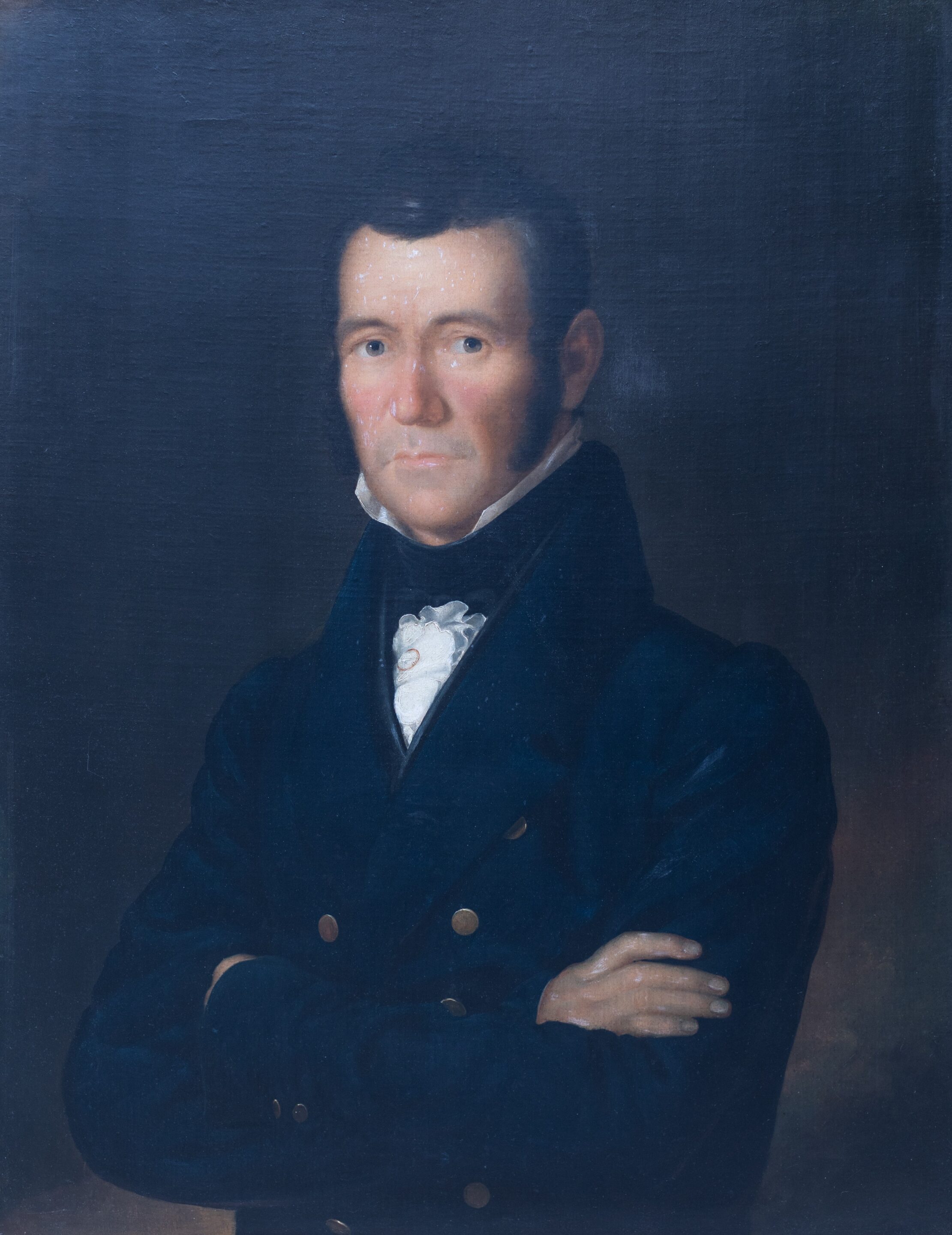

The Rt. Rev. William Meade (1789-1862) lived long before the age of selfies and photography. No one knew what the third Bishop of the Diocese of Virginia looked like as a young man until his large oil portrait, and his wife Thomasia’s, showed up in the backseat of a Subaru in Richmond this year.

The portraits were a gift from his descendants to the Diocese of Virginia.

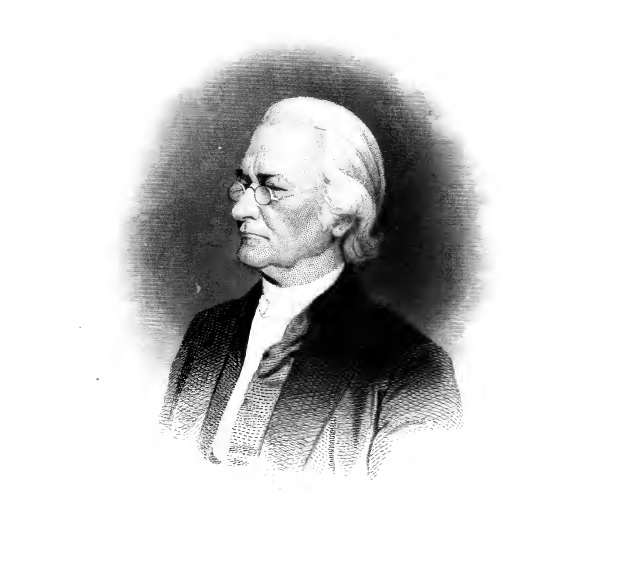

“We have a lot of drawings and engravings of Bishop Meade when he was older; this is the first time we’ve had a painting of him when he was younger, and as far as his wife, I do believe this is the first image we’ve had of her, the first I’ve ever seen,” Diocese historiographer and registrar Nathan V. Madison said.

The paintings are just shy of 200 years old, Madison estimated.

“What a stroke of luck!” he said. “That someone several states away but with familial ties to Virginia, happened to have portraits, unique in so many ways, of a bishop and his spouse whose portraits we were lacking! And that they were generous enough to donate them to the Archives and ‘bring them home,’ as it were. A great experience and an amazing gift to the Diocese itself.”

For donor Jaye Richey, who is 80, handing off the portraits brought on “a mixture of relief, a little sadness. I knew in my heart it was the best thing we could do.”

Meade Matters

A founder of Virginia Theological Seminary, Bishop Meade holds particular significance as “an interesting and complicated, but nonetheless important figure in the Diocese’s history,” as well as to the history of Virginia, according to Madison.

“The third Bishop of Virginia, his episcopate lasting from 1841 to his death in 1862, he was a prolific writer, and one of his works in particular, Old Churches and Families of Virginia (1857), remains an invaluable source regarding both Diocesan and state history, and has seen a number of reprints over the last century and a half,” Madison said.

“He fought against several ideas that were spreading through some churches at the time, particularly those of the Oxford Movement. Near the end of his episcopate, though an opponent of secession, he did side with Virginia and the Confederacy during the Civil War and aided in the formation of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America, participating in that church’s only consecration of a bishop during its brief existence.”

Need for Meades

“Who wants the Meades?” Richey asked her children as she prepared to make changes to her small Cape Cod-style home in Riverside, Conn., near Greenwich.

When no one expressed interest, Richey decided that “it was time to take them back home.”

The portraits represented her late husband Samuel Hunter “Spike” Richey II (1944-2022)’s long-ago family connections to the South. He was a cradle Episcopalian who loved to sing in the choir. She soon joined the church.

While the family moved often and lived for a time in the South, they always identified as Northerners. “We are all displaced Yankees,” she said.

Her husband’s father was John Meade Richey (1920-2004). The portraits changed hands before resurfacing one summer when his stepmother called from Long Island “and announced that she had these portraits, and would we like them?” Jaye Richey recalled.

All their walls were covered with pictures, but the Richeys went to get the Meade portraits and make space for them in their TV room. The paintings were heavy from the oil and multiple ornate frames from later restorations. In their Connecticut home, they hung out for about a dozen years, facing the TV and a bookshelf.

“You blend it into the home,” Richey said. “I knew how important these portraits or people were to him and had been to his dad and grandparents. I know he was happy to have them. I grew used to them and liked them.”

The painter did not sign the portraits, and Richey didn’t see any resemblance passed down through her husband. She eventually read about Bishop Meade and was impressed by the distances he traversed in an era when Virginia stretched to the Ohio River.

“Talk about business trips,” she said. “When your Sundays are covered, it takes all of Saturday to get there, and most of Sunday afternoon to get home. You cover a lot of ground. That’s a commitment.”

Outstanding Artifacts, Personality Insights

Madison called the portraits “outstanding artifacts to have received, on any number of levels.”

“I was struck by a few things, most of all though the quality and detail of the portraits,” he added. “Just from looking at their portraits, you can almost get a sense of who these people were, their personalities; just remarkably well painted. These were apparently personal paintings, as opposed to ‘official’ Diocese portraits, so I also believe you get a little more of the ‘person,’ as opposed to the office, in Bishop Meade’s portrait.”

Such a personal depiction at this age helps to understand William and Thomasia Meade more fully.

“Most of the imagery we have of Bishop Meade is from his later years,” Madison said. “These portraits, however, were painted when he was younger – judging from the style of dress, his apparent youth, and the fact that his wife was painted as well, I believe these were produced during his time as Assistant Bishop, between 1829 and 1836, the year Thomasia died, and several years before he became Bishop Diocesan.

“The fact that we also have a portrait of Thomasia, the only portrait of a bishop’s spouse in our collection, and the only image I’ve seen of her in general, is also amazing,” Madison added.

“In 1857, Bishop Meade published a small, limited-run book entitled Recollections of Two Beloved Wives, which provides emotional insight into Meade as a man, but it also provides such a wealth of information regarding Thomasia, who she was and her role in her husband’s ministry. Thanks to her portrait, we can now apply a face to the person.”

On the third floor of the diocesan offices, Madison is curating a museum space with all the bishops’ portraits, including now the Rt. Rev. William Meade oil portrait. A new section of portraits may detail the roles women have played in the history of the Diocese “and my goal is to have Thomasia placed there, as well, so both can be publicly viewed,” he said.